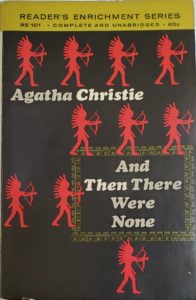

As I finish reading one book and look through the thousands of books in the house to choose the next one(s) to read, of late I’ve been looking for books I not only want to read but that I can discard (through sale, donation, or trashing) when I’m done. A couple of months ago I found one of those in Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. I wouldn’t have known where this book came from or how I obtained it had I not found in it a Christmas gift tag with my handwriting. I gave it to my sister some years ago, probably when we were teenagers. This particular printing was November 1964. It is a student copy, which suggests I bought it during my sister’s high school years.

I admit to this being my first Christie book to read. I’ve see a number of movies made from her books, but had until this never picked one up to read. That is now rectified, and the enjoyment I found from this volume guarantees I will read more of her writing.

Originally published in Christie’s native Great Britain in 1939 with a different title, a very vile title (that I won’t enter here) by today’s standards, it has sometimes been published in the USA with the title Ten Little Indians. Like Christie’s main writing, it’s a murder mystery. In this case, however, you don’t know if the murders are really murders, until the denouement.

Ten people are lured to an island off the southern coast of England named Indian Island. Ownership of the island is in question and the ten, as they are making their way there, have lots of questions about who owns it now. They are invited by a person they don’t know: U.N. Owen. Seven men and three women arrive on the island within a day or two of each other. Eight are guests, two are servants. All expect their host, Owen, to arrive soon. As they head towards the island, we get some backstory on several of them. For others, backstory comes out as the novel progresses.

In each guestroom is a poem, framed and hanging on the wall, titled “Ten Little Indians”. It’s a childhood diddy at least some of the guests recognize. On the table in the dining room are ten Indian figurines. The ten people meet for their first evening meal. After it the butler, following written instructions from Owen, who he’s never meant, puts on a phonograph record. It turns out to be a surprise, someone speaking (not music), who indicts each of the ten with a death they have caused in the past, saying that they would have to pay for it.

How each character pays for it comes out chapter by chapter. The first happens that night, as one of the guests dies of poisoning. Murder? Or suicide? The remaining nine speculate. An elderly judge who is a guest takes charge and “holds court,” trying to work the problem logically and find out what evidence they have. The guests all become suspicious of each other. Meanwhile, one of the Indian figurines disappears.

By the time Christie wrote this, standards for detective novels had changed in, say, the forty years since Doyle had given us Sherlock Holmes. Then, the means of solving the case wasn’t given in the writing. Since then, by Christie’s time it was expected. So in the novel should be the means for the reader to solve it, if you read closely.

I was close. As the ten, one by one, meet their untimely end, I came to the conclusion that one of the dead wasn’t dead but was really alive, but was only thought to be dead by the other guests/servants. I had a candidate, but it turned out I was wrong. I suspect, however, that if I read it over again, slowly, I would see that the right clues were there from the start. That’s probably impossible to do, given that I’ve read the Epilogue that explained it all. Re-reading it would be an interesting exercise.

I never will do it, though. The story and plot were good, the writing was good, it was an easy read, and I highly recommend it. But I have too many books in the house, too many I want to read, and thus have to be very picky about the ones I will re-read. No, this one will go to the get-rid-of pile as soon as I post this. Very glad I read it—actually I should say “we” read it, as my wife and I read it aloud together, the 183 pages plus some of the 32 page reader’s supplement in ten sittings—but it’s goodbye, ten little Indians. I hope another reader someday acquires you and derives the same pleasure from you that I did.