About a week ago, when I thought my heart surgery would be today, I began going through books that I would want to take to read. It may be a pipe dream to think I can read much while in the hospital, but I want to be prepared. I’ve picked out one book on prayer and two books of letters. These are print books. I have a fair number of e-books I can easily pull up on my phone.

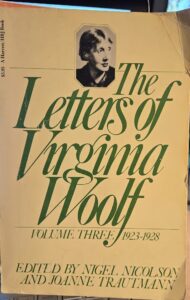

One book of letters is The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Vol. 3, 1923-1928. I picked this up used quite a few years ago and kept it on a basement shelf, waiting for the right time to read. Well, that seems to be now. It’s a thick paperback to be holding in bed. But the letters are, for the most part, short. I’ve read 40 or 50 pages into it to make sure it’s a suitable volume to read in my circumstances. So far I find it is.

I read a couple letters yesterday, and found an interesting item.

Importunate old gentlemen who have been struck daily by ideas on leaving their baths, which they have copied out in the most beautiful, and at the same time illegible handwriting, dump these manuscripts at the office, and say, what is no doubt true that they can keep it up or years, once a week, if the Nation will pay £3.3 a column. And there are governesses, and poetesses, and miserable hacks of all kinds who keep on calling—So for God’s sake write us something that we can print.

I need to add a little context. Virginia Woolf and her husband, Leonard, were part of a literary group known as the Bloomsbury Circle, or Bloomsbury Set, who had great political and literary influence in the first two or three decades of the 20th century. Leonard had just been appointed literary editor of The Nation and Athenaeum a magazine that dealt with British politics and English Literature. Virginia was, at that time, heavily involved in the Hogarth Press, print a variety of books. Leonard was also involved in that.

Thus, they were busy people. Virginia wrote a letter to Robert Fry on 18 May 1923. Leonard had been less then a month in the editorship, and the couple had just returned from a month-long holiday in Spain and France. Leonard’s plate was full, with coming up to speed at the magazine and dealing with book publishing. Complicating this appears to be a glut of unsolicited submissions to The Nation, submissions that Virginia, in her letter to Fry, considered as from “miserable hacks”. And she begged Fry to “write us something we can print.”

I find it funny almost that this is the same complaint editors have today. Too many submissions from unqualified writers crowding the mail and e-mail inboxes. Given the universality of typing now, they don’t have a lot of “illegible handwriting” to decipher, but reading those many submissions is not easy. Nor is it a good use of time. So most of those submissions go unread, or get shoved off to an intern with instructions such as, “If you’re still reading it after one page, put it in my inbox; if you’re still reading after three pages, bring it to my office right away.”

This should make all authors take some time before they make unsolicited submittals. The editors probably put you in the category of know-nothing writer, and expect nothing of publishable value from them. You’ve wasted your time submitting like that. Instead, take a long time to hone your writing skills, study the market, study the publishing outlets, study the realm of literary agents. Then, after however many years that takes, start submitting in a smart way.

I found it interesting that, in 1923, the problem editors faced was that same as they face today—with illegible handwriting thrown in. Technology makes the process easier, but the problem remains.