Approximately two years ago, when I began reading in earnest as research for Documenting America: Making The Constitution Edition, I read something, not in a source document, about the Founding Fathers being interested in the writings of John Locke, particularly his two Treatises on Government, published anonymously in 1689. I figured I’d better read them, as background for my other research. So, I found a good quality electronic copy (for free), downloaded it, and began reading.

Let me say two things to start. My reading of this was probably not in an optimum way. I read in fits and starts wherever I had a few moments of waiting with my phone, the device I read the whole thing on; and I probably wasn’t at my best as I read it. I don’t know that I retained much about the two treatises, and will someday have to read them again.

This post will be only on Locke’s Part 1. Part 2 will follow in another post in the not-too-distant future.

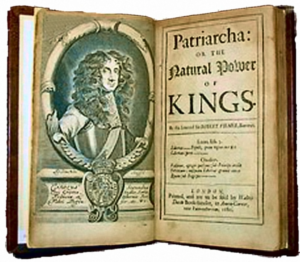

Part 1 was…strange. Somehow the Preface didn’t stick with me. I got into the book, and Locke is referring to “Sir Robert”, giving quotes and page numbers. I had no idea who he was referring to. At some point I had to go back and re-read the preface. Locke referred to Sir Robert Filmer, who had written a book named Patriarcha: On the Natural Power of Kings, published in 1680. In this, Filmer laid out the case for the divine right of kings and an absolute monarchy. He got some of his material from Thomas Hobbes in a 1651 book named Leviathan.

Locke said his purpose in writing his Part 1 was “to establish the throne of our greater restorer, or present King William; to make good his title…” Locke liked William, taking note that he came to the throne in what is called the Glorious Revolution of 1688. His mother was the daughter of King Charles 1st of England, so he had some place in the royal order of succession. He married his cousin, Mary, daughter of the Duke of York. William and Mary came to the throne as joint monarchs, and after Mary died in 1694 William reigned alone until his death in 1702. Some thought him to be an illegitimate king.

It’s not my purpose to go into this history, but a little of it is essential background for Locke’s Part 1. From the wording of the Preface, it’s as if Locke had a foregone conclusion and was trying to justify it with this book. However, I don’t think that’s the case. He looked at Filmer’s work, was horrified by it, and decided to refute it. That also had the result of justifying William’s reign.

As I said, the book was strange to me. The language and structure, being archaic, made the reading somewhat difficult. It seems Filmer’s argument for the divine right of kings/absolute monarchy came from the Bible. He believed Adam was born king, was thus king of all his progeny, and passed that right through his progeny. Locke gave many arguments against this, using different scenarios to refute Filmer’s different points.

Except, they all sounded the same to me, these different points. Filmer said Adam, by right of being first born of all creation, had an absolute right to rule over first his children, then their children, then that was passed down to them and their children. Locke said no, essentially that was ridiculous. That once a child reached age of majority, or responsibility, the father no longer had any right to rule over him.

One thing I did take away from this Treatise, though which I was had been better developed, is the concept of man is either born a slave (per Filmer) or born free (per Locke). It’s a continuum, with slave on one side and free on the other. I’m assuming Filmer chose the slave side, and hence, as slaves, all mankind is servant to whoever holds the legitimate kingship. Locke rejected that. Maybe he did state the continuum thought clearly, and in my diminished reading capacity I missed it. I’m going to look for that again for sure.

Over and over this went, for 200 pages. Shades of claims by Filmer and counter-claims by Locke. It started to all run together. Perhaps, had I read in better conditions, I would have felt it more informative. No, informative isn’t the right word, but I can’t think of a better one. I didn’t take as much away from it as I’d hoped to.

I believe the framers of our country and government were most interested in Locke’s second treatise, which dealt with government. They were opposed to monarchy, so could probably not have cared less about Locke’s defense of King William in the first treatise.

I have this as an e-book, in my Google Books account, so I’ll keep it. I’ll read it at least one more time. Except, I feel that I ought to read Filmer before re-reading Locke. And, possibly, I’ll have to read Hobbes before I read Filmer. And, I imagine when I read Hobbes I’ll find he relied on someone else and I’ll have to read that.

Where does it end?