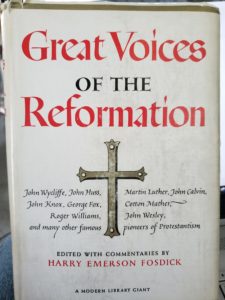

Some books sound good when you make a decision about buying them, but upon reading, turn out to be difficult to get through. Such was the case of Great Voices of the Reformation. Edited by Harry Emerson Fosdick, t

his is a 546 page hardcover from 1952 that I picked up used somewhere.

The premise is good. Look at the people who were the main clergymen of the Reformation; give a brief bio of each and description of their publications; and provide lengthy excerpts of their writings. The documents included were mainly doctrinal writings.

Fosdick began with John Wycliffe, then John Huss, then Martin Luthor. From there he moved on to mostly familiar names, such as Zwingli, Calvin, and Knox. But he included some names I had either never heard of or hadn’t associated as being significant parts or the Reformation. One example was the Anabaptists, represented by a number of names I had never heard of. Another couple were Cotton Mather of New England fame and Jeremy Taylor of the church of England. I’d heard of both, but just hadn’t thought of them as main forces in the Protestant think tank.

One surprise was Roger Wiliams. He founded my native Rhode Island when he was banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony. I

learned about him in school, but hadn’t thought about him in years. I found his writings refreshing and his colonial methods better than many others. He believed in buying land from the Indians rather than just taking it. He was also in favor of religious freedom. This contrasted with the Puritans, who wanted freedom for their own worship but not for others—at least not in their own colony.

Part of the problem with this book was the archaic English in some of the writings. Most of the oldest texts have had the English modernized or been translated into modern English. However, I suspect they kept the English purposely a little archaic, for I found it difficult to read. Some was sentence structure, not necessarily the words.

Another difficulty was how the writers had approached their subject matter. It’s hard to explain, but the older documents tended to put me to sleep. I would settle in my reading chair in the sunroom at noon and open the book to John Huss. Knowing his story was so inspiring, I had high hopes, but I fell asleep more than once after reading a page or two. I should probably chalk that up to my failure, not the failure of the document.

The later writers—George Fox, John Woolman, and John Wesley, were definitely easier to understand. I’ve read a lot of Wesley’s works independent of this book, and, being last in this volume, it was enjoyable to wind up and end up with a familiar voice.

I had thought this was to be a reference book, permanently in my library. After reading it, however, I think it i unlikely I’ll ever come back to it. I made some marginalia in a number of places. Before putting it on the discard pile, I’ll flip through the pages and see if I should copy out anything for reference.

I give the book 3-stars. Maybe had I read it at peak powers of comprehension, it would have been 4-stars. Certainly, if you are interested in the history of the Reformation, especially the doctrinal views of the major participants, pick up a copy. Of course, everything in this book is in the public domain (except the biographical introductions written by Fosdick) and available on the internet without too much search.