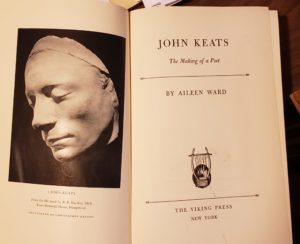

In July, while looking around for a book to read—a book I would find interesting yet wouldn’t want to keep after reading, I saw on my bookshelves in the storeroom John Keats: The Making of a Poet. By Aileen Ward, published in 1963, this was perfect. It looked like serious biography, the subject of poetry still holds my interest, and I didn’t think it would be a book I’d like to read twice.

Born in 1795 in London, son of a groom/stableman, Keats was one of the “Romantic era” poets. The last major one to be born and the first to die. Before reading this, I knew his poetry and read some of it. I have, somewhere upon my over-stuffed bookshelves, a small volume that someone pulled together of best-known works, and a volume of his complete poems.

But I knew little about the man except about his tragic death from consumption at age 25. This book told me much about him. His father was a hard worker who opened a business for stabling the horses of travelers; he died when Keats was 9 and away at boarding school. His mother was a gadfly who quickly remarried upon her husband’s death, left the family for a few years, then returned in time to have Keats nurse her through the final stages of consumption when he was a teenager.

Keats took up the study of medicine and seemed to do well with it. He was at the point of launching into one of the lower-level medical sub-professions when poetry became his main interest. He began to write it and found he could do it. Alas, he fell under the influence of Leigh Hunt, who was roundly disliked by the better known literary critics. Hence Keat’s first poetry book, published in 1817 while he was still planning on a career in medicine, was also denounced by those same critics.

Despite this, Keats laid aside the medical field and took up poetry as his vocation. His long poem, “Endymion,” published and panned by the critics, is not considered a classic. According to Ward, many of his shorter poems were autobiographical, written about this or that person, or place, or event. The most famous of these is “On First Reading Chapman’s Homer”.

But Keats struggled financially, as well as in his health. He never received his full inheritances from his parents and grandparents, never earned much from his published poems, and lived without extravagance.

This biography does a good job of telling all of this, sometimes in almost too much detail. But it does keep moving and did keep my reading. I read about 10 pages a day in my noon reading time, in the sunroom our outside in the woods when the weather cooperated, and finished it in a little over a month.

I found the sources used by Ward and her way of spinning them into the story particularly impressive. Despite how old this is relative to our modern times (Keats died in 1821), it seems she was able to document close to every day of his life: when he wrote which poem and why; where he traveled; who he dined with; what his health was like at the moment. It helped that Keats left an extensive correspondence behind at his death.

I am so glad I saw this book on the shelf and read it. I rate it the full 5-stars. I’ll not read it again and it’s not a keeper. But learning about this little piece of poetic history has acted like a tonic in my reading life.