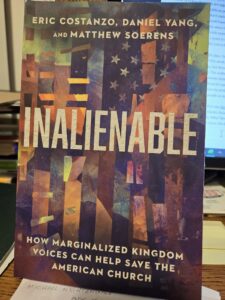

Back in January, I went to an event at our church titled: “How to Navigate the 2024 Election Year”. The evening involved dinner and a book, as well as a guest speaker. His name is Eric Costanzo, and one of the books to choose between was his, Inalienable: How Marginalized Voices Can Help Save The American Church, coauthored with Daniel Yang and Matthew Soerens. That’s the one I chose. The event was okay, not great. I wasn’t sure what to expect. I went mainly to be supportive of our pastor.

So I read the book, taking over a month to go through it. It was published in 2022, which means it was mostly written in 2020 and 2021. I found the book a little difficult to read. One was the frequent references interspersed—but the authors said in the first chapter they would do that, so it wasn’t a surprise. The other was the frequent use of buzzwords. I have a internal buzzword meter that is kind of fine-tuned. Use a buzzword once and I ignore it. Use it twice and I get a little irked. Use if four or five times in every chapter and I have to fight the urge to puke. That’s where this book is.

The first chapter takes the place of an introduction, with the title “Why the American Church Needs Saving”. Very early comes the phrase, “many evangelical Christians in the United States have silently tolerated or openly embraced nationalism, sexism, and racism, ‘compromising our values for power.” That’s pretty clear for the premise they hope to prove.

Since I am part of the evangelical church, I guess he’s talking about me. Seems that whatever I—we—have done in our Christian walk is all wrong. Yet, in the entire 221 page book, they skirt the issue of who is responsible and give no action steps other than listen to the voices of the “global south,” which is defined in the book as those parts of the world lying south of white Europe and white America.

In an attempt to not offend people, they don’t give names of who is to blame. It’s clear that they are opposed to the evangelical church’s embrace of right-wing Republican politics. They condemn that embrace, as I do. But they don’t mention names, and they really don’t get into specific issues. It would have been nice for them to have picked a date, place, and time when the American church started to go bad to the point that it needs saving, because, assuming they are correct, that would give us a point in time to go back to, figure out what we did wrong, and make corrections going forward.

As to racism, the point is well taken. Sunday mornings tend to be the most segregated moment of the week, and that’s sad. Why is that so? The book didn’t really say, but they strongly imply it’s white racism that is the root cause. The authors seem to imply that forced diversity is the answer. I’ve always been a proponent of natural diversity, where, as an individual of reasonable intelligence and loving care, I come to recognize my prejudices, set them aside with God’s help, and embrace all people as equals before God.

To me it seems wrong-headed to say, Hey, our congregation is too white. We need to find some blacks, Asians, and Hispanics to reach out to. But I may not know any. Why? Simply because in my day-to-day roamings—to the grocery store, the doctor, on my walks, or wherever the chores of a given day take me—I may not meet people who are different than me, or the circumstances may not be right for discussing church with someone.

The other, main problem I see in the book is the continuation of the war on the individual. My review is much too long already, but throughout the book the authors work in that the existence of marginalized groups is due to individualism. I reject that, but explaining why will take more than one post.

Two other things about this book that irk me. While it includes many references to and quotes from their primary sources, the notes are endnote rather than footnotes. I hate endnotes. If it’s important enough to make a reference to it, it’s important enough to have it right on the page where I can easily see it without flipping a hundred pages away. And second, it does not include a list of suggested reading. The quote from probably two hundred sources (see the endnotes to find the names), but don’t suggest the 5, 10, or 20 that will help the reader the most in continued study of what’s wrong with American evangelicalism.

As it is, I give the book 3-stars. I almost gave it 2, but I realize the authors are trying to do a good thing here and address a problem they see. I’m not discarding the book. I hope to read it again, in the not too distant future, in hopes of learning something I missed, and to better understand the authors’ opinions.