I haven’t said much about this recently, but our son is Dean of Students at the Law School at the University of Chicago. He’s been slowly working his way up through university administration since he earned his PhD in 2011, a degree he worked long and hard for.

In past positions (not at the Law School) he’s had a lot of interesting things come up, such as a student who presented letters saying he was a C.I.A. operative and therefore needed some type of special treatment. Or such as the student who forged her admission papers, showed up at registration, and tried to force her way into enrollment and housing. Some things weren’t so benign, such as student deaths to deal with when Dean on Call.

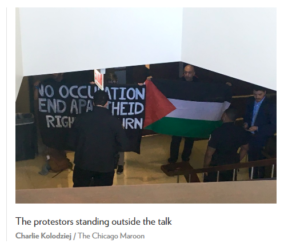

An interesting situation came up on April 9, 2019, when pro-Palestinian protesters interrupted a talk by a pro-Israel speaker. The talk concerned the boycott of Israel wanted by Palestinians. The talk was by a visiting professor. The Palestinians entered the room and began shouting, preventing the speaker from continuing. Someone called the campus police. Charles was close by in the law school, and so came down and tried to restore calm and allow the talk to continue. You can read about it in this article in The Chicago Maroon, the university newspaper.

Embedded in the article, in tiny print, is an e-mail Charles sent to the students later in the day, explaining what had happened, what his actions were, and how all this applied to University policy, especially the policy of free speech. I particularly liked this from his e-mail:

The heckler’s veto is contrary to our principles. Protests that prevent a speaker from being heard limit the freedoms of other students to listen, engage, and learn.”

This brings me to something concerning free speech that I’ve been thinking of for quite some time. It’s relevant to me now as I work on my next book, Documenting America: Making The Constitution Edition, especially in relation to the discussions on the Bill of Rights. Freedom of speech is covered in the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble….

As has been pointed out many times, the Constitution was written in a way to restrict the government, not the people. Laws of Congress restrict the people, but not the Constitution. Over time this has been re-interpreted as applying to the people as well. In certain areas, people must restrict their behavior based on the provisions of the Constitution.

What about in this case? The professor who was speaking has a right to free speech. The protestors who were preventing others from hearing him have a right to free speech. Do those in the audience have a right to hear the speaker? Is there any free speech when hearing is prevented?

Which brings me to something I’ve thought of for a long time. The right of free speech doesn’t guarantee the one speaking or publishing will have an audience. This, I think, is sometimes a problem with the press, especially the broadcast press, who decry alternate voices that crowd them out when they consider themselves to be “legitimate” news outlets and the others not. Sorry, but no one executing their right of free speech or free press has the right to an audience. No one.

But what about those who came to hear the speaker? Do they have a right to hear? I’m not sure. Certainly civility would say that they ought to be allowed to hear the speaker they came to hear, and that the protesters should find a different way to protest. Silently holding signs, confronting the speaker before and after speaking, establishing an alternative talk in another place. These would all be ways for the protesters to be heard and seek to gain their own audience.

This brings me down to what I’ve been thinking about: when rights clash. I have freedom of speech, but not where that right clashes with someone else’s right. I have freedom to practice my religion, but not where that right clashes with someone else’s right.

In a clash of rights, whose right should come out on top? Maybe before I ask that I should say, when rights clash, find a way to accommodate both people’s rights. Then, if you somehow can’t do that, whose right should come out on top? In the USA we have always said it should be the right of the weaker person.

I hope our nation always takes that position. The government was established to protect our God-given rights. When the rights of two people clash, and when no reasonable accommodation of both can be found, then the right of the weaker person should prevail. I can think of one huge area where, in a clash of rights, the Supreme Court and some of the States have come down on the side of the stronger party, but that will be a subject for a different post and perhaps a different blog.