Dateline 1 Oct 2020

In January of this year I began writing The Teachings, the third (chronologically) novel in my Church History series. I had been reading for research some time before that. I worked on it consistently through January and February, then bogged down in March. My problem was I wanted to be historically accurate to events in 66-70 A.D., but didn’t want to overdo the historical stuff and not have the novel interesting for the characters and the plot. I started re-reading my main source, Josephus, but that just made me more uncertain of how to proceed.

So, as I have a habit of doing, I went to another project, my family history/genealogy research into the children of John Cheney of Newbury (1600?-1666). Genealogy research is always a pleasure and I figured it would be a brief, rejuvenating diversion. Some years ago I began this work on his youngest child, Elizabeth, who married the mariner Stephen Cross of Ipswich. I found much about them (mainly about Stephen, but that helped define Elizabeth’s life as well), and realized it would be a stand-alone book about them. I brought that book to about 60 pages in 2018, then set it aside. In March I picked it up again as the diversion, and by April 3 I had it up to around 80 pages and, I thought, close to finished.

On April 3, Lynda went into the hospital with her burst appendix and was in 19 days, requiring two surgeries. It didn’t look good for a while. Since due to the pandemic I couldn’t be with her at the hospital, to keep myself occupied I worked feverishly on the Cross-Cheney book. Before long I had it up over 100 pages. Lynda finally came home though was still weak and recuperating. I got the book up to 116 pages, polished it, and published it. So far, with 1 sale, it’s doing about as expected. A few of the figures were of poor quality, so I haven’t advertised it to the Cross or Cheney genealogy boards and won’t till I get those figures replaced.

After getting my diversion done, it should have been back to The Teachings, right? Well, a little bit. But soon I was working on another diversion. It started as decluttering, going through the many papers my mother-in-law left behind at her death. But that soon evolved into transcribing our Kuwait years letters. That took the better part of August and early September. That’s now done. I will someday turn that into a book for my children and grandchildren. That will take editing, adding commentary, and illustrating it with photos. I don’t see doing more on that for the rest of this year—although, I don’t rule out occasionally opening the file and adding some commentary.

That brought me up to mid-September. Time now to work on The Teachings. Except I still didn’t feel like it. I decided I would take another Amazon Ad Challenge in October, and that I would focus on the first Documenting America book as the next to advertise. But this book needed significant work. It was the first I published, long before I understood formatting. I also figured I should add new material to bring the book up to date for 2020. I worked on this the second half of September, and began the re-publishing process on Sept. 28th. The last couple of days have been sufficiently busy with life that I haven’t had much time to work on it. But that’s now a today task for the e-book. I’ll have the proof copy of the print book on Saturday, so by Sunday Oct 4 the re-publishing process should be complete.

Then what? Work on The Teachings, finally? Maybe, maybe not. I want to get the Cross-Cheney book figures corrected and that book re-published and advertised. There’s always file maintenance. Plus, evenings in front of the television, I do e-mail “maintenance” and saving my correspondence to Word documents. That’s a tedious but fun process, something I can do multi-tasking, a non-urgent item to make progress on. But next on the list of items I posted on Monday is The Teachings. Will I finally get back to this?

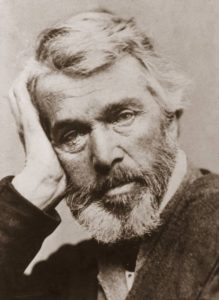

Today, instead of working on finishing the Documenting America changes, I dusted off my Thomas Carlyle Bibliography. Last night, as part of my TV-watching-multitasking, I opened the Carlyle Letters On-line and read a couple of letters. I discovered a short translation he did of a Goethe autobiographical passage that wasn’t in my list of his writings or publications. How could this possibly be? I have three other full Carlyle bibliographies, plus a partial bibliography that covers the period in question. Why would they leave this out? I documented it on paper and, since it was late, went to bed.

This morning, as my first item of business after devotions, was to add this entry in my bibliography. First, however, I found the document on-line, at a previously unknown (to me) site called the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Sure enough, in the January 1832 issue was the Carlyle translation. I checked the two thick bibliographies on my shelf and confirmed that this composition wasn’t in it. Maybe they didn’t add it because it’s a translation with just a paragraph of Carlyle commentary rather than an original piece? Maybe so, but those bibliographies include his other translations. I added all this to my bibliography. While I was at this, I found an essay on Carlyle I hadn’t seen before and downloaded it for future reading.

The fact that I keep pulling off my novel in favor of other, less important publishing tasks, is perhaps testimony that I’m not thrilled with how the novel is going. Or that it’s consuming a lot more brain power and I’m unwilling to expend that brain power at present. I’m not sure what it is, but, if I ever hope to get this novel completed and published, I need to get on it. Even if it takes a lot of brain power.

Stay tuned to find out if I manage to get to it.