Post #2 in my Wisdom from Dad series

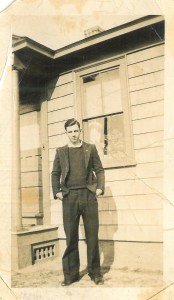

My dad was strongly shaped by the Great Depression. Born in 1916, he went to school only through 8th grade. If he entered school at the normal age we think of today, and progressed on schedule, that would mean he “graduated” about 1930. The worst of times was yet to come, but it was pretty bad that year, with no hope for relief in sight.

At some point Dad went to work for “Old Man Angel”, on his farm in East Providence, probably in the Riverside area. Dad said he earned “a dollar a day plus my dinner.” I’m not clear, so long after Dad told me that, whether this was the job he got after he left school, or if perhaps this was a summer job while he was still in school. I don’t know if that matters. He worked five full days a week, plus a half day on Saturday. What did he do with his $5.00? Took it home, gave $4.50 to his mother for support of the family (he had four younger siblings), then went to Labby’s store. There he took his 50 cents and bought his treat with it. He alternated between as many grapes as 50 cents would buy, or as much ice cream as it would buy. He sat outside the store and ate the grapes or ice cream.

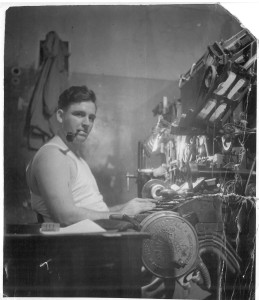

This is the story Dad told, more than once. I believe him. Dad didn’t stay out of school. He soon entered trade school to learn the trade of linotype operator. Hot lead machines that set the type for newspapers or magazines. I’m not sure how many years this school might have been. Dad learned his trade and learned it well. As soon as he graduated from trade school, he went to work at

the Delmo Press in Pascoag, R.I., working there until he went in the army for World War 2, and for a brief time after the war till he went to work for the Providence Journal.

My guess is Dad probably graduated from trade school around 1933 or 1934. This was now some of the darkest days of the Depression. No doubt Dad felt himself fortunate to have a job, and to keep it. They say the Depression shaped the Greatest Generation into being a frugal lot. My dad was an extreme case of this. The young man of 1936 would not have sat outside Labby’s store and eaten 50 cents of anything in one sitting. He would have denied himself any treat and put the 50 cents in the bank. He was that way until he died in 1997. After Mom died and we kids were out of the house, he lived cheap.

How cheap? I could write post after post of how he lived. I’ll give two examples. He did the coupon thing at the grocery store. I imagine he’d love the couponing shows we have now. But, not only did he use many coupons, he tracked his savings, writing down how much he saved and keeping a running total each calendar year. On our phone calls he would often say what his current amount saved for the year was. In true frugalness, he didn’t keep this on a pad of paper. Pads were something you bought new. Dad would never be so extravagant as to do that. No, he took envelopes he received in the mail—bills or junk mail—slit them open, and used the inside and back of the envelope to keep his tally.

The other example was how he would look for dropped change on the ground, usually when he walked his dog. He knew where to look. At the gas station he looked around the air pump and vacuum machine. “Especially after the snow melts,” he told me. Around the newspaper box was another place. It always surprised him how people could drop money and not be bothered to bend down, search for it, and pick it up. But other people’s carelessness was his gain. And, he tracked how much money he found on the ground—and wrote it and added it, you guessed it, on the back of an envelope.

That was all introduction. With us kids, our allowance started when we were 8 years old (I think he started my younger brother a little younger, with a smaller amount). At 8 we received 25 cents a week. It wasn’t a gift. We did chores for that. It doubled every two years, so that at 10 we received 50 cents, at 12 a dollar, at 14 two dollars, and at 16 the whopping sum of $4.00 a week. It stayed there so long as we were in school, even if we had a job. As soon as we left school, the allowance stopped.

As soon as we received the allowance, we had to keep track of our money. Dad made each of us three kids matching banks, just different enough that we could tell which one was ours. Each Thursday, which was his payday, we had to present our “accounts,” and, if the total in our little notebook didn’t add up to the amount of money in the bank, we would not receive our allowance.

You think I’m joking? Not one bit. Week by week, year by year, for eight years, we kept our accounts, and Dad checked them. If we had a discrepancy, we made sure to find it first, figure out if we had bought something we’d forgotten to write down, and wrote it. Each entry had to have a date. Now, before you think Dad was hard on us, I think he often relented when our money didn’t add up. He would help us to remember where it went. Or, if we lost money, he would allow us to write “lost” and an amount, recalculate, and give us our allowance, with a promise to do better next time.

When we reached 16, and our allowance went to $4.00 a week, we no longer had to account for our funds to get our allowance. Dad wrote in our books, something like Your 16 now. If you haven’t learned how to handle your money by this time, I can’t help you any more. And, he added encouragement to be frugal, responsible, and disciplined in our approach to money.

I can’t tell you how happy I am that Dad put us through this discipline. I won’t say I’ve done it as rigorously now as I did when the every-Thursday reckoning came around. But I still track my funds. I still balance my checkbook. If the amount is off by even a penny, I search until I find the mistake. I keep a spreadsheet of every non-cash purchase, but including cash withdrawn, and put them into categories, add them up. If they don’t match the total in the checkbook, savings, and H.S.A. account, I have to find the discrepancy. I kind of wish I had saved my account notebooks (they were small—the kind that fit in a shirt pocket—and my bank. They would be nice keepsakes now.

I wonder if my biggest failure as a parent was that I didn’t keep this discipline with my children. Of course, for a time their accounts would have been in dinars and fils, rather than dollars and cents, but, hey, it’s still money. Maybe, even without this, I transferred some sense of the right way to be disciplined with money. I hope so.