My first characteristic of what makes the United States of America different than most other nations is the concept of self-determination. In other words, we chose our own form of government and our own leaders, and have maintained that for over 230 years. Actually, the choosing of our government goes back much further than that.

From the moment that Europeans came to these shores in the early 1600s, selection of leaders through voting has been a part of our nature. The form of government was at first based on what the colonists knew back home, or what was imposed on them by the terms of the charter by which the colony was established. However, slowly, the form of government changed and settled into a pattern.

First it was pure democracy at the local level, with a fledgling republic at the colony level. By the time of the revolution, when the colonies considered themselves states, republican form of government was well-established. At the local level even, a mini-republic had mostly replaced democracy. Some vestiges of democracy remained, but for the most part the form of government was a republic.

Of course, a republic requires active participation of its citizens in terms of voting. At regular intervals, from as short as six months to as long as two years, the people chose their leaders. In doing so peacefully, the people were saying, “We are satisfied with this form of government. All we are doing now is choosing those who will lead us, either returning those already in leadership or voting new ones in.” Election after election, for more than a century before we were a nation, this process took place from New Hampshire to Georgia. Those eligible to vote chose new leaders and kept their form of government.

Self-determination. We will govern ourselves. How different this was than in the Europe they had left! England had a monarch, a king or queen, who ruled. In the 17th Century the parliamentary system was flexing its muscles and growing in importance. England went through three revolutions (one bloody, two peaceful) and one counter-revolution. All other European nations had much the same. The monarchy was a coercive power. The people didn’t choose it so much as the king ruled by “divine right”. France, in a bloody revolution that would eventually lead to a worse dictatorship than the kings ever were, would throw off that monarchy thirteen years after the American Colonies declared their independence. Other nations would eventually follow suit. But it was the bloody American Revolution that set much of that in motion.

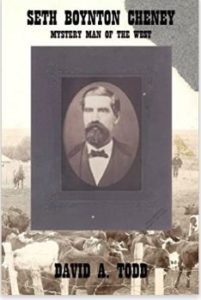

As I researched my first genealogy book, Seth Boynton Cheney: Mystery Man of the West, I had occasion to look into town records of Waterville Vermont, where Seth was born and raised until he was 13. It was interesting to see the notices of the town meeting on the last Saturday in March (right in the middle of maple sugar harvest no less) and having all voters required to attend. I read how they set the tax rate: “Voted to establish the rate at $X” or “Voted a rate of $Y to construct a fence around the cemetery.” These people were governing themselves at the local level, deciding big issues as a democracy but electing representatives to lead the municipal republic the rest of the year. I “watched” as new towns were formed, Waterville carved out of Bakersfield because the Waterville residents couldn’t cross the snow-covered mountain in March to attend the town meeting. Self-government in action, the form of government chosen by the people and maintained year by year, decade by decade, century by century.

As I researched my second genealogy book, Stephen Cross and Elizabeth Cheney of Ipswich, I saw the same thing from a much earlier period, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the years 1647 to 1710. I actually went back earlier than that, as I was simultaneously researching an earlier ancestor in the Cheney family, the subject of a future book. I saw the same thing with the town, and more so at the county and state level. One rabbit-hole I went down with my research that took place during Stephen’s and Elizabeth’s lives was the change in colonial charters forced upon the colonies by the king of England. This did not go over well. In fact, the seeds of the American Revolution were sown right here, as people, who had chosen and maintained a form of government they liked—self-determination—had a form of government and leaders forced on them—a coercive power—who served at the whim of and benefit of the monarch, not the people. Ipswich was a hot spot about this and some consider it to be the cradle of American independence.

Now, in 21st Century America, we have a hard time conceiving what the world was like during our colonial days. Oh, we know from studying our history what the colonies were like, and may have a vague understanding of England, from whence most of those settlers came. But I think we need more study of just how different the government was in our world. And to what extent the people had, not just the right, but the obligation to maintain that government through votes and taxes. We had our faults back then, and took far too long to address those faults. Compromises would eventually be forged that would keep us as one nation rather than several regional federations, compromises that later would almost tear us apart.

Yes, I believe self-determination is a defining characteristic of the United States of America. Other nations now have it. Yet many other nations only dream of it. It defines the USA. How long can we keep it?