I’m usually reading several things at once. I have a reading pile in the sunroom, where I go around noon most days to get a break from my tasks. That reading usually consists of printed books, and sometimes a magazine. I have a reading pile in the living room as well, and a basket of magazines I’m way behind on. This is usually evening reading, after all else is done for the day.

Then there’s my phone, through which I read using a Kindle app, a Nook app, and Google books. My phone I might use anywhere, and the things I read on it usually are easier reads. That may not be the best description. But I think they take a little less concentration and can be read in places such as waiting rooms, restaurants, coffee shops, etc. Any place I have a few minutes and want to engage my mind with more than people watching.

So yesterday, I read a little more than normal, and to my surprise, I finished reading four different items on the same day. How odd is that?

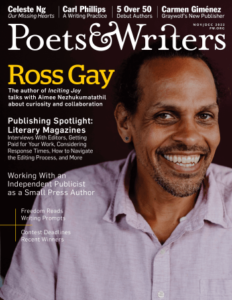

In the sunroom, I finished reading an issue of Poets & Writers magazine. I buy one of these at Barnes & Noble from time to time. While this mag is very much oriented towards the Master of Fine Arts crowd and is far from my writing world, I enjoy it more than other writing mags. Anyway, I had only two pages left in this particular issue, and finished those pages yesterday. At a future writers meeting I will pass this along to someone.

Still in the sunroom, I next looked at an essay I’ve been slogging through on Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Years ago I downloaded this from the Bulletin for Biblical Research and printed it (at a time when the company I worked for had a generous policy of making personal copies). I may have read most of it before but, having come across it in a notebook while working on my near-continuous dis-accumulation efforts, I decided it was time to read it, absorb what it said, and get rid of it. The essay is about 60 pages long, heavily footnoted.

While I enjoyed reading it, the article was a bit of a chore to get through. When I started yesterday, I had about ten pages left to read. Maybe I had come to an easier part of the magazine, or maybe my mind was better engaged, but I got through those last pages. I’m not quite ready to discard the sheets, but within a couple of months I’ll extract the info I need from it to go into a future Bible study I plan to write.

Then, in the evening, I finished the last nine pages (of 633 total) in a biography of David Livingstone. This tome took me three months to get through, though admittedly I laid it aside several times to read other things. Other than the small print, and smaller print on the extensive quotes from Livingstone’s letters and journal, it wasn’t a hard read. Ten pages at a time was fairly easy to get through. And if I hadn’t been reading other things simultaneously, I think I would have been able to finish this in a month. It’s done now, and will likely take two blog posts to review.

Lastly, I finished re-reading Volume 1 of the correspondence between Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Years ago, long before Google Books and Kindle, I found this at Project Gutenberg, downloaded both volumes, and formatted them in Word for a blend between tight printing and easy reading. Using those printing privileges, I printed them and put them in notebooks. Meanwhile, I have recently learned how easy it is to upload a Word document to Kindle for your personal library. I did that with Vol. 1.

As I’ve said many times before, I love reading letters. Wanting something “light” for those odd moment reads, I sent this to Kindle and began reading it perhaps a month ago. I found it delightful, as I did perhaps 20 years ago. Yesterday, I came to the end of Volume 1.

This is sort of waste-of-time reading, since I have so many things to get through. But it was quite enjoyable. I was able to read it fairly quickly, including in the hospital last week with Lynda. At some point yesterday, I read a letter by Emerson to Carlyle, and was surprised to find it the last in the volume. So I promptly found Vol 2 on my computer and uploaded it to my Kindle library. Not sure when I will start this.

So, that’s the story of the strange circumstances that had me finishing four very different reads on the same day. It’s unlikely to ever happen again.

Time to pick up some new reads. One I’m already 40 pages into. What else will I pick up next?