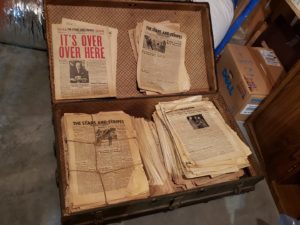

Of the many things our parents left us, or came to us in other ways, I think the most burdensome is photos.

Photos? Yes, photos. Those pesky little glossy things, or some matte finish, depicting people of long ago, houses once owned or lived in, vehicles once driven, and landscapes visited. No doubt those who left them to us thought, “What a treasure this is for our children (or grandchildren), to see great-aunt Matilda all dressed up for the derby. Oh how they will cherish them.”

Except nobody now alive ever met great-aunt Matilda. Only those who studied the family genealogy knows who she was and how she fits into the family relationships. And only those who ever will study genealogy will ever care.

Photos tend to add up. Just looking at the photos on Lynda’s side of the family, I estimate that we have 8,000 photos. No, I’m not exaggerating. That’s probably 3,000 from her dad’s side and 5,000 from her mom’s side. Just looking at her dad’s side, he was something of a hobbyist photographer. He inherited various family photos from his parents, who got at least some of them from their parents. He looked at those old photos, some as tiny at 2×3 inches, and had enlargements made; then multiple copies of the enlargements; then smaller copies having the developer play around with the tint and border and resolution. So one tiny old photo marked “Jacob’s Well” on the back was shown to be a photo of his grandfather’s family, showing two older men, one older woman, and seven children (the youngest not yet born)—some on horses, some standing on the rocky landscape.

Jacob’s Well is a feature in Clark County, Kansas, now incorporated into a park. Except we’ve visited the park—not every square inch of it, mind you—the landscape looks more like what you see at the family ranch in Logan Township, Meade County, Kansas. I could believe the photo is mis-labeled, except another family member in another branch that didn’t even know each other until 2015 has a copy of the exact same 2×3 photo and it is also labeled “Jacob’s Well.” What to do?

Is this photo a keeper? Surely it’s the Cheney family, but how do you identify the people? One of the older men is the father, Seth. The other is uncle Frank Best (most likely). The older woman is mother Sarah, the youngest child Rose, the older girl Cora. But which of the others are William, Clarence, James, and Walter? We can make an educated guess, based on size. But these people were all standing at least 20 yards away from the cameraman. There’s really no way of knowing who’s who.

The photo is from 1898, based on Charlie, the youngest child, being born in 1899. The question becomes: how important is it to keep this photo? And the multiple copies of the enlargement? And the multiple copies of different tints, borders, and resolutions?

This has come up now because another family member, who didn’t want the photos when Lynda’s dad died in 1996, has accused us of hoarding them because we didn’t drag them out every Thanksgiving and Christmas so that we could look at them “as a family.” Now he wants to look at them, divvy them up, and do so at a high school reunion in July. Even though we would have to impose on a relative for a venue. Even though Lynda was thinking she didn’t particularly want to go to the reunion. And actually, the demand to go through the photos included the 5,000 from the other side of the family. It is physically impossible. Reunions are times to see friends, swap stories, share meals. How will it be possible to sort through these photos and make decisions on their final resting place on a reunion weekend, even if you layover a couple of extra days? You can’t; it’s impossible. And some day, we’ll have to do the same with all the photos we took over the years.

So we are going through them. Album by album, box by box, folder by folder. After three weeks, we can see a little light at the end of the tunnel on the 3,000 (estimated) from the dad’s side, and have made some progress, at least to the point of knowing what we have, on the mom’s side. Duplicates have been identified and those we want removed from the overall collection as keepers. The albums have been checked and are currently being re-checked. Four other albums have been consolidated into two and are ready for re-checking. We are very close to boxing the non-keepers and shipping them to this family member with a note saying, “We’re so done with these; keep what you want, destroy the rest.” The other 5,000 will hopefully follow in about two more weeks.

Yes, destroy them. Our kids won’t want them. We don’t know anyone else’s kids that want them or even want to see them.

What was meant to be a blessing, and what served as a blessing to three or four generations and maybe 100 people, are now a burden. Let them die a peaceful death.